Last week, I wrote about Special Dividends, those instances when a company gives shareholders a dividend outside of the regular dividend-paying cycle. Regular dividends are, of course, an increasingly important way for companies to attract shareholder interest, but there’s another strategy that’s used—especially during periods of economic downturns—to reward shareholders. And that’s repurchasing shares of the company stock, or stock buybacks.

And some companies do both—particularly blue chip stocks.

Stock Buybacks vs. Dividend Payments: Should a Shareholder Care?

First, let’s look at regular dividends. Consider dividends as a profit-sharing plan, paid at a known cycle to shareholders, and amounting to about one-third of total shareholder return since 1932, according to Standard & Poor. Dividends are a long-term commitment on the part of a corporation. The downside is that dividends are paid-out after tax by corporations, and then shareholders are taxed when they receive them. Double-taxation, if you will. The advantages are obvious—free money, and if you hold those stocks in a retirement plan, you can defer the taxes until your golden years, when your tax bite will probably be lower.

[text_ad]

A buyback is when a company repurchases its own stock just like you and I would do—in the market. Investors like stock buybacks because they reduce the number of outstanding shares and also enhance the company’s per-share profitability measures, such as EPS, Return on Equity and cash flow per share. Over time, those better ratios will often lead to higher share prices, adding to investors’ pocketbooks. And, the buyback isn’t taxed until the stockholder sells his shares.

And following a stock buyback, it’s not unusual for a company to increase its dividend, and that gives shareholders a further bonus.

From a corporate standpoint, buybacks are optional, so the company has a choice in what to do with its extra cash—it is not obligated to repurchase shares. Whereas with a dividend, if a company changes its dividend policy adversely (by lowering or eliminating its payments), the share price can suffer a devastating drop, with shareholders running for the exits.

The timing of a buyback is also important. Companies want their buybacks to look like a show of strength—confidence in the company’s future. And while share prices can—and often do—rise after a buyback, if, for some reason, they took a dive, the buyback may be considered a failure.

And if the shareholders believe the company should be investing their excess cash back into the growth of a company instead of repurchasing shares, the buyback could backfire.

As well, a company might use stock buybacks to camouflage the number of shares it’s handing out to its top executives in the form of stock options. The buybacks may balance out the options issuance, keeping the total number of shares constant, and essentially not benefiting the shareholders.

Which Method Rewards Shareholders the Most?

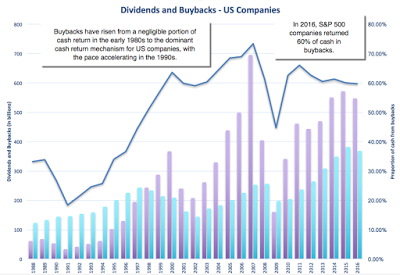

In recent research, Professor Aswath Damodaran, from New York University, noted that in 1988, “almost 70% of all cash returned to stockholders took the form of dividends and by 2016, close to 60% of all cash returned took the form of buybacks.”

Source: Aswath Damodaran, Professor of Finance at the Stern School of Business at New York University

For the six years from June 2009 to June 2015, $2.7 trillion worth of shares of S&P 500 companies were bought back.

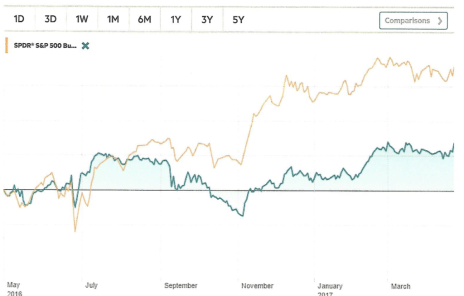

As for performance comparisons, you can see by the following chart, that since 2016, the shares of companies that have repurchased their shares (as represented by the SPDR S&P 500 Buyback ETF (SPYB)—the gold line) have outperformed the Dividend Aristocrats (represented by S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats (SPDAUDP)—the green line, stocks that have raised dividends for at least 25 years).

So far this year, the SPDAUDP has returned 5.8%, a bit better than the SPYB’s 4.98%. But the Buyback Index significantly beats the Aristocrats in one-year total return—18.46% compared to 7.2%.

As you might guess, that has not always been the case. For a 14 ½ period from January 2000 to June 2015, the return for both indexes was almost identical, with the Buyback Index gaining 9.90% and the Dividend Aristocrats Index up 9.89%.

Consequently, whether or not you are a buyback fan, the research shows that at least for the past almost-15 years, buybacks and dividends can both pay off in enhanced returns to shareholders.

And stock buybacks just seem to be hitting their stride this year. So far in 2017, according to rttnews.com, there have been more than 100 stock buybacks. Here is a list of recently announced buybacks, in just the past two weeks:

| Date | Company | Amount of Buyback | P/E Ratio |

| 5/1/17 | Cognex (CGNX) | $100 million | 49.86 |

| 4/28/17 | Royal Caribbean Cruises (RCL) | $00 million | 18.08 |

| 4/27/17 | Intel (INTC) | $10 billion | 15.66 |

| 4/26/17 | NetGear (NTGR) | $3 million | 21.31 |

| 4/26/17 | Interface (TILE) | $100 million | 26.22 |

| 4/24/17 | Ameriprise Financial (AMP) | $2.5 billion | 15.56 |

| 4/20/17 | CSX (CSX) | $1 billion | 27.92 |

| 4/20/17 | JB Hunt Transport (JBHT) | $500 million | 23.37 |

| 4/20/17 | Visa (V) | $5 billion | 44.81 |

| 4/18/17 | Xinyuan Real Estate (XIN) | $40 million | 4.42 |

Source: rttnews.com

As you can see, the list covers a variety of industries, and several companies who have seen their shares significantly rise in the last year. As always, this list is just a beginning point for your research. And since these industries are comprised of many companies with excess cash right now, it may be a good reference for investigating other companies in the same sectors who have yet to announce stock buybacks.

[author_ad]