Philanthropy in Philadelphia

Albert Barnes and Edwin Fleisher

One Great Biotech Stock ---

Note: Today’s title may be interesting to word-lovers because of the two words’ common roots. The name Philadelphia, coined by founder William Penn, means “City of Brotherly Love,” while philanthropy is giving (usually of money) for the good of mankind (or, again, brothers).

And this is my topic today because I’ve just returned from a visit to Philadelphia that was enriched by the work of two philanthropists in particular, one well known and one less so.

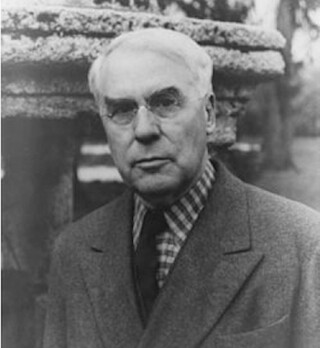

The first was Albert Coombs Barnes, who was born into a working-class family in the city in 1872 and earned his medical degree at the University of Pennsylvania.

Albert C. Barnes

In 1899, with a German chemist named Hermann Hille, Barnes developed a mild silver nitrate antiseptic solution that was effective as a treatment for gonorrhea and as a preventative of gonorrheal blindness in newborn infants. Within five years of starting the business in 1902, the firm cleared $250,000 in profits (roughly $6.1 million today). Barnes bought out Hille’s interest and in July 1929, he sold the business for a reported sum of $6 million (roughly $81 million today).

The move was well timed on two counts. First, the stock market peaked just one month later, and second, antibiotics would soon prove superior to Barnes’ silver nitrate.

Barnes had begun collecting art as early as 1911, with the assistance of one of his former high school classmates, the painter William Glackens, who had been living in Paris. But it was the combination of the sale of his business and the Depression that enabled Barnes to amass what has turned out to be one of the world’s premier collections of art.

“Particularly during the Depression,” Barnes said, “my specialty was robbing the suckers who had invested all their money in flimsy securities and then had to sell their priceless paintings to keep a roof over their heads.”

Barnes’s collection grew to include 69 Cézannes—more than in all the museums in Paris—as well as 60 Matisses, 44 Picassos and an astounding 178 Renoirs. The 2,500 items in the collection also include major and minor works by (among others) Henri Rousseau, Amedeo Modigliani, Chaim Soutine, Georges Seurat, Edgar Degas and Vincent van Gogh.

The collection was originally displayed in a mansion Barnes had built to house it, in suburban Merion Pennsylvania, and operated as an educational foundation, not a museum. I saw it there about five years ago; it’s a very nice neighborhood.

But Barnes was too much of an original thinker to be part of the establishment. He displayed his paintings alongside traditional Pennsylvania-Dutch chests, African carvings and medieval, Renaissance and Early American hinges and metalwork so that viewers could compare color, texture and pattern.

And he never catered to the privileged, or to art historians; he cared more about the student.

So he limited access to the collection, requiring people to make appointments by letter. In a famous case, Barnes refused admission to James A. Michener, who gained access only by posing as an illiterate steelworker. In another, Barnes turned down the poet T.S. Eliot’s request with a one-word answer: “Nuts.”

But Barnes didn’t have the last word. He died in 1951 in an automobile accident. He and his wife had no children.

And over time, money grew tight. Both the building and the art works required conservation, but the Foundation was handcuffed by Barnes’ will, which stipulated that the Foundation was to remain an educational institution, open to the public only two to three days a week. Furthermore, the art collection could never be loaned or sold; it was to stay on the walls of the foundation in exactly the places the works were at the time of his death.

Also limiting the Foundation’s options was the fact that the residential neighborhood had long limited parking and public access in order to preserve neighborhood character.

So the Foundation decided to relocate the collection—now valued at somewhere between $20 and $30 billion!—to a new building to be constructed in Philadelphia, and after numerous and lengthy legal battles, the Foundation prevailed, supported by the City of Philadelphia and funding from major regional foundations, including “The Establishment” that Barnes was so opposed to.

The new museum is located near others, such as the Rodin Museum and the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Franklin Institute science museum. The building is a modern masterpiece, and the work is displayed exactly as Barnes originally specified, but it looks and feels better, because there’s more space and far better light.

Most important of all is that the Barnes Collection is now accessible to far more people. I highly recommend it. And if you can, I recommend that you view the work surrounded by as few people as possible. The best way to do that is to visit either at the end of the day or at the very start, as my wife and I did.

---Advertisement---

If This Week’s Trades Don’t Hand You at Least 30% Profits in 60 Days—You Won’t Pay a Dime

Cabot Top Ten Trader’s results have left our readers smiling all the way to the bank, with profits of up to 50%—coming in as little as 30 days. All thanks to breakout winners like these ...

* Continental Resources 122%

* Encore Aqua 101%

* Cleveland Cliffs 93%

* DryShips 95%

* McMoRan Exploration 91%

* M&F Worldwide 78%

Don’t wait until after the next economic reports come out or the big profits will have passed you by. If you’re serious about grabbing your share of gains from these trades, now is the time to join us ...

---

My wife and I found our second philanthropist quite by accident.

Right next to the Barnes building is the Free Library of Philadelphia, chartered in 1891 and in its current building since 1927. We walked in to have a look around, enjoyed a great visit to the Rare Book Department and then spied a sign that pointed to the Fleisher Collection.

We had no idea who Fleisher was, but we found out.

It started with Simon B. and Moyer Fleisher, the sons of German Jewish immigrants, who founded one of the country’s first worsted woolen mills in southwest Philadelphia. Originally called the Fleisher Yarn Company, the establishment became a world leader in hand knitting yarns and worsted fabric—and generated a lot of money for the founders’ families to work with. One family member was their son Edwin A. Fleisher, who founded the “Little” Symphony Club in 1909 with 65 children ranging in age from 7 to 17. Fleisher welcomed all youth regardless of race, creed or sex. He supplied the sheet music for performances from his private collection. And as the orchestra grew, Fleisher’s collection grew!

Fleisher purchased copies of virtually every known orchestral performance set available in the United States, before traveling to Europe in 1913 to acquire new music he was unable to obtain in America. He made three more trips abroad, including a three-month sojourn to Russia on a special passport to procure orchestral scores. And by 1929, his Collection had outgrown his ability to house it. So he donated it to the Free Library of Philadelphia.

During the Great Depression (while Barnes was buying paintings), Fleisher worked to obtain and publish orchestral scores by contemporary American composers, using WPA money to pay the salaries of more than 100 copyists.

And the Fleisher Collection continues to grow today, under the guidance of Dr. Gary Galvan, who was sitting at his desk as we wandered in, and proceeded to enlighten us about the collection, which is arranged on shelves that seem to occupy every usable inch of his corner of the library; just from where I was standing, I saw many shelf-feet of Tchaikovsky, with his named spelled three different ways.

Here’s a photo of Gary (purple shirt at left) in his domain, addressing members of the Conductors Guild.

The Fleisher Collection is now the largest source of orchestral performance sets in the world, with more than 21,000 titles, and is thus the premier source for composers, conductors, instrumentalists and researchers.

Many of these scores are irreplaceable, as the originals were lost to the vagaries of time, fire, flood, war and politics, particularly in Europe and Russia.

Yet the Fleisher Collection lends them freely to institutions all around the world, for a modest fee.

In March 2013, the collection circulated 1,997 scores and parts!

For music-lovers, it’s a fun trip.

---

Moving on, it appears that the long-awaited market correction has begun; how long it will last and how far it will go are yet to be determined. Yet tracking individual stocks can still pay off, because I don’t think this bull market is finished. One strategy is to look for stocks hitting new highs, but the problem with that is that at times likes this, when people are running for safety, that can lead you to defensive stocks.

I prefer to look at growth stocks that had previously been strong, and that are holding up well in the face of potential selling pressures.

BioMarin Pharmaceuticals, for example.

Trading as BMRN, the stock looks rock-solid here, hanging around its 25-day moving average.

We last recommended the stock in mid-November in Cabot Top Ten Trader, where editor Mike Cintolo wrote the following:

“BioMarin specializes in rare genetic diseases, and currently maintains a portfolio of four approved treatments … The company also has a pipeline of very promising genetic treatments, in particular drug candidate GALNS, which is designed to treat people with Morquio syndrome—a rare genetic disorder that causes problems like abnormal heart and skeletal development … Clearly, GALNS isn’t going to impact BioMarin’s bottom line any time soon, but with Wall Street already starting to price in the drug’s potential impact, investors would be smart to take a closer look at this rising biotech star.”

Mike continued, “BMRN was off to the races last week in the wake of the GALNS news. The stock broke out above former resistance at the 44 level to trade in all-time high territory just below 50. Prior to the surge, BMRN shares were already headed higher in a steady uptrend along support at their rising 50-day and 200-day moving averages … Buying dips in the current market environment is recommended, while a stop loss on a trade below 44 should help limit losses.”

And that was great advice! Since then, BMRN has climbed from 47 to nearly 63, and for the past month it’s been trading between there and 60, pausing for a rest while the broad market gets a little crazy.

I think this is a decent entry point, so you could just buy here and cross your fingers. But if you’re serious, you’ll take a no-risk trial subscription to Cabot Top Ten Trader and get Mike’s latest advice on the stock.

Yours in pursuit of wisdom and wealth,

Timothy Lutts

Editor of Cabot Stock of the Month