Some generalizations about the stock market have acquired the status of law over the years, but when a market trend contradicts that law, it can take investors a while to catch up.

It’s the same phenomenon that used to rule in academia (before the internet speeded everything up), when we used to say that it took five years for a department to build its reputation, but 10 years to lose it. It takes longer for a segment of the market to lose its rosy reputation than it did to get it.

[text_ad]

Take biotech stocks, for instance. Biotech’s reputation as a producer of great growth stocks was built during a remarkable run from the moment the broad market turned around from its Great Recession lows in 2009 to the middle of 2015.

Here’s what the long winning streak in biotech stocks looks like in a monthly chart of iShares Nasdaq Biotechnology ETF (IBB). Except for one four-month dip in 2011 and a sharp pullback in early 2014, IBB hardly hiccupped as it soared from 58 to 400 from March 2009 to July 2015.

Any sector that delivers a nearly 7x advance over a period of more than six years will win a (nearly) permanent place in investors’ hearts.

But when you switch to a daily chart of IBB since its July 2015 top, you see the problem that biotech investors face.

Biotech stocks are facing the inevitable that always follows years of enthusiastic investment, especially when a few of the biggest winners collapse. As an example, here’s what has happened to Celgene (CELG), a major biotech stock, during the same period, as it slipped from its July 2015 high at 141 to support in the low 90s in 2015 and 2016 and is scrubbing off much of last month’s gap up as investors rotate out of growth stocks.

So what’s the answer for biotech stock investors? The first answer is to start tracking what sectors are actually doing, not what they have a reputation for. Anyone who enjoyed the long run in IBB, for instance, should have started reducing their exposure during the ETF’s free fall last January, if not sooner.

The second answer for biotech investors is to watch individual biotech stocks rather than sectors. Yes, ETFs make it easy to ride a long trend and put bets on a group of stocks rather than just one. And the standard wisdom is that spreading your investment around on a group is a lower-risk proposition than buying single stocks.

But making a lower-risk investment can also lull you into a false sense of security. I would bet that there are a ton of investors out there who are sitting with their sector bets on biotech and telling themselves that the sector will come back … eventually.

And eventually that may be true. But in the meantime, sector investors will be keeping their money in a losing proposition and missing the opportunities that come from looking at individual stocks.

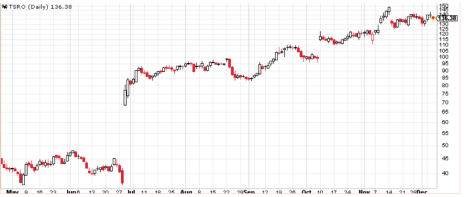

Here’s a chart of Tesoro (TSRO), a Massachusetts biotech developer of cancer treatments. The company announced in late June that Niraparib, a treatment for recurrent ovarian cancer, had scored a big win in late-stage clinical trials. You can see the gap up from 37 to 81 that followed the announcement.

But the chart also shows the stock’s continued rise to 136 as investors kept buying the story.

If you’re wondering how you might find stocks like Tesoro, the answer to that is also simple. Cabot Top Ten Trader found TSRO for subscribers back in October, when it was trading at 121.

Like all successful growth investors, Cabot Top Ten Trader doesn’t buy sectors or industries. Mike Cintolo, who picks the stocks for Top Ten every Monday, looks only at the stocks that really worked during the previous week. These are the stocks that are leading the market, with no regard for sector or industry or which index is leading the market.

Mike calls it reality-based stock analysis, and it’s the answer to the problem of making assumptions about what ought to be working in the stock market.