High yield bond returns have been quite strong. But the yields are lower than they’ve been in 30 years. And that makes them even higher risk.

High yield bonds, often referred to as junk bonds, have credit ratings below “investment grade;” that is, below BBB- (at Standard & Poor’s) or Baa3 (at Moody’s). The low credit rating is produced by heavy debt loads or volatile or no profits at the underlying companies. In terms of claims on the company’s assets, high yield bonds rank below more senior debt but above common stock. As such, high yield bond performance tends to be similar to that of equities (with considerable sensitivity to economic conditions) rather than that of investment grade bonds.

The attractiveness of high yield bonds can be measured by two traits. First, their absolute level of yields. A bond yield of 8%, all other things equal, is more appealing than a yield of 3%. And, second, their yield is in excess of risk-free Treasuries, which is termed “spread.” A yield spread of 5 percentage points above Treasuries is more interesting than a spread of only 4 percentage points, regardless of the level of interest rates.

[text_ad]

An additional, subjective measure of attractive-ness is the degree of collateral protection provided by bond covenants, which can support the bonds’ value if the company goes bankrupt. The most favorable time to buy high yield bonds is when the economy and financial markets are struggling. Bond prices are low, reflecting investors’ heightened aversion to the risks and reality of elevated defaults. In recessions, the default rate may rise to 8% to 12%, compared to normal times when the default rate has averaged between 3% and 4%. The weak bond prices also provide appealing absolute yields (an 8% yield, for example, generates a 24% cash return over three years) and spreads over Treasuries. In periods of distress, spreads have reached 8 percentage points, and surged to as high as 20 percentage points in the 2008 financial market meltdown. Importantly, companies issuing new high yield bonds readily accept more restrictive covenants, which reduces investors’ downside risk. Once an economic recovery arrives, high yield bond prices typically rebound and yields and spreads shrink.

High Yield Bonds Have Been on a Tear

Recent high yield bond returns have been strong. Over the past five years, high yield bonds have generated an annualized 35.7% rate of return. This remarkable rate exceeds the robust 24.3% rate for investment grade corporate bonds and the otherwise impressive 16.2% rate for the S&P 500. Most of the high yield bond gains have been driven by higher bond prices, which have been fueled by strong economic conditions and falling Treasury yields, along with a shrinking yield spread over Treasuries. The higher coupon rate for these bonds also helped propel returns.

Today, for investors, high yield bond conditions are the polar opposite of favorable. High yield bonds now yield about 4.5%, with a 3.61 percentage point (or 361 basis point) spread above Treasuries. This spread is approaching 30-year lows. Covenants are weak or non-existent (“covenant-lite” is a common industry term nowadays).

What is motivating investors to load up on high yield bonds, despite the narrow advantage? The surging economic recovery and an unquenchable thirst for yield in the near-zero interest rate environment. Critically, the belief that the Federal Reserve will backstop the bond market and that the government will provide economic stimulus if conditions get dicey has structurally altered investors’ perception of the risks of high yield bonds. If this belief holds true, then the small yield premium will have been worthwhile.

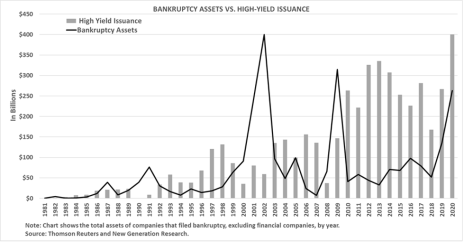

Taking advantage of this belief, companies issued a record $400 billion in high yield bonds last year, with the hefty pace continuing this year. American Airlines, recent issuer of $6.5 billion in fresh high yield bonds at a blended 5.575% interest rate, had to turn away offers to buy as much as $45 billion.

Combined with $3.5 billion in new leveraged loans, American’s $10 billion debt-raise was the largest in industry history, despite the company’s daily $30 million cash outflow. The airline may never be able to repay this debt, which is on top of its $32 billion in existing debt. American is by no means the only zombie-like company that could face bankruptcy if the future generosity of bond investors is tested by higher interest rates, credit market distress or a recession.

With yields and spreads currently heavily compressed, high yield bond investors must rely on price appreciation to generate meaningful profits. The recovering economy may help bonds retain their lofty prices by reducing the chances of defaults, but rising interest rates will weigh on any upside potential in bond prices. And, unlike stocks, the most a bond holder will receive at maturity is par value. Just as the return opportunity is limited, the risk potential is elevated. Investor enthusiasm leaves little room for all-too-common disappointments that seem to arrive every five to 10 years.

Today, like “working holiday” and “original copy,” high yield bonds have become an oxymoron – there is very little “high” about their yields. We view this as a time to be more fearful than greedy. Yet, prospective investors should be preparing now for when conditions become more favorable – the window of opportunity can close quickly in an era of aggressive government support.

Do you own any high yield bonds? How have they performed? Tell us about them in the comments below.

Editor’s Note: This post was excerpted from a recent issue of Cabot Turnaround Letter. To read more, click here.

[author_ad]