The Dow Jones Industrial Average rose almost 1,200 points Thursday, following a better-than-expected inflation report. The stock market has had a good month, after a mostly declining year. Investors on the morning business shows sounded almost giddy—with relief and joy!

And I love it! But do I trust this sudden wellspring of market madness? Not really. I hope it’s for real, and believe me, I’m going bargain hunting, too, but I’ll also keep a reserve of cash—just in case.

I’ll be buying individual stocks, as well as exchange-traded funds. But one area that I’ll be avoiding until after the first of the year is mutual funds. And there’s a very good reason why you should too.

[text_ad]

Mutual Funds Distributions Can Turn into a Huge Capital Gains Bite to Your Portfolio

Mutual fund managers buy and sell shares of the securities in their portfolios all year long—some more than others. You can figure out how much selling they do by looking at the fund’s turnover ratio. The turnover ratio can range from 0% to 100%. That’s right; some funds buy and sell constantly. And the higher the turnover ratio, the more likely it is that you will see significant capital gains in that fund and big distributions at the end of the year if most of the sales resulted in gains. Of course, the opposite could be true, if the fund manager is a lousy stock picker or ran afoul of a declining market!

But many funds hold their positions long term. That means significant appreciation and dividends can accrue over the years. And that can be a double-edged sword when the fund sells those positions at a gain. 1) your portfolio will greatly benefit from the gains; but 2) you’re going to get taxed on any distributions every year, as well as gains when you eventually sell the fund.

You see, by law, mutual funds must distribute the dividends and capital gains that have built up in their funds by the end of every year, even if those gains were reinvested in the fund and they haven’t sold any shares. Dividend distributions arise from dividend and interest income on the securities in the fund. Net capital gains distributions are comprised of gains from the sale of any of the fund’s securities, minus any realized losses (including losses carried over from prior years).

That means that if you own a mutual fund on the day the distributions are made, you are going to be taxed on them—no matter when you bought the fund (even if it was the day before). If that’s the case, you will be taxed on what’s called “phantom income”—income you never received because you didn’t own the fund during the year it was accumulating the gains.

Here’s how this works: During the year, the fund manager buys and sells stocks within the fund’s portfolio. If the stocks sold result in an overall gain, without enough losses to offset the gain, the fund’s investors receive the difference, which is then taxable.

And even if most of the year’s markets were in the doldrums (as in 2022), if the fund began the year with prior gains, and the fund manager sold stocks to capture those gains, there may be capital gains distributed at the end of the year.

Added to that, because markets have risen so much in the last quarter of the year (provided they keep going up!), you could be caught in this tax trap if your fund manager quickly sold some of the stocks in the fund to capture those gains.

Lastly, and very importantly, you should know that if the stocks sold were held less than one year, you will most likely get hit with owing regular income tax on those, as the capital gain tax (0%, 15% or 20%, as shown in the table below) applies only to assets held more than one year.

Capital gains tax rates for 2022

| Long-term capital gains rate | Taxable income |

| Single filers | |

| 0% | $0 to $41,675 |

| 15% | $41,676 to $459,750 |

| 20% | $459,751 or more |

| Married filing jointly | |

| 0% | $0 to $83,350 |

| 15% | $83,351 to $517,200 |

| 20% | $517,201 or more |

Source: IRS

The funds generally make their announcements of the gain estimates in late October or early November and then begin paying them out by the middle of December. Once you receive a mutual fund’s estimate of distributions, you have until the “date of record,” or the last day to be listed for a payout, to make any ownership changes.

Steps to Reduce the Distribution Tax

All is not lost. There are some steps you can take to reduce this end-of-the-year tax on your portfolio.

- Buy your funds in your IRA, 401k, or other tax-deferred savings account. That way, you won’t be taxed until you withdraw them, since investors in tax-advantaged accounts don’t pay taxes on dividends and capital gain distributions in the year they are received—as long as they keep the money in the account and don’t withdraw any of it.

Wait until January to buy any new funds, or at least until the fund is ex-dividend. Ex-dividend means the stock is trading without the value of the next dividend payment; it trades on or after the ex-dividend date.

The other advantage to buying the funds ex-dividend is this: Once the dividend and net capital gain distributions are made, the net asset value (NAV) per share of the fund drops by the amount distributed. Now, if you are an existing shareholder in the fund, that doesn’t mean you’ve lost money, as you’ve already taken the distribution in cash or reinvested the money in additional fund shares purchased at the lower adjusted NAV. And if you reinvest your distributions in the funds at a lower NAV and the shares rise, you’re a winner!

But if you decide to invest after the distributions with the lower NAV, you won’t have to pay the distribution tax, and you are set for appreciation if the fund rises in value.

Reinvest your distributions. Those reinvested distributions are considered part of your cost basis, which can reduce your taxable gains when you sell your fund, especially if you’ve held the fund a long time. Here’s an example from T. Rowe Price that shows how this strategy can reduce your taxes in the long run.

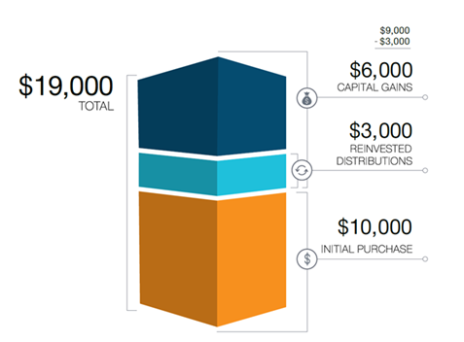

“Suppose you bought $10,000 of an equity mutual fund on January 1, 2017. Over the next five years, the fund paid distributions totaling $3,000, which you reinvested in the fund account and included on your tax returns. When you sold all your shares on July 31, 2022, you received $19,000—$9,000 above the $10,000 you originally invested. But you wouldn’t pay taxes on the whole $9,000 since you had already been taxed on the $3,000 of distributions over the prior five years. You would only include $6,000 as your capital gain on your 2022 tax return.”

(Fig. 1) Hypothetical Capital Gains Scenario with Reinvesting Mutual Funds’ Distributions

This example is for illustrative purposes only and does not reflect the performance of any specific investment.

Source: troweprice.com

4. Engage in some tax-loss harvesting. That means if you are sitting on some investment losses, now may be the time to sell them an offset those losses against any fund distributions. You can’t wait until January; you have to do it before the distributions are made.

5. Invest in tax-efficient equity funds, which are managed with the goal of limiting capital gain distributions. They do this by keeping turnover low and using tax-loss harvesting to offset any realized gains.

6. Sell your funds before the mutual funds’ distributions to avoid the tax due. You would have to pay taxes on your gains, either ordinary income or capital gains, depending on how long you have held the fund. You can always re-enter the fund, but be aware of the “wash sale” rule, which says that if you repurchase shares in the same fund within 30 days, you can’t claim a capital loss for that tax year.

These are merely suggestions. I’m not an attorney or CPA, so please make sure you check with your tax advisor to see if any of these scenarios will benefit your overall long-term investment plan.

For more insight into financial planning, personal finance, and stock market investing subscribe to Cabot Money Club today!

[author_ad]