Interest rate expectations have shifted quickly of late, as traders tried to anticipate how changes in geopolitics, economic data and financial markets would affect Fed policy. You may have noticed the ripple effects of these moves in your own portfolio, impacting utility stocks and other income investments. You should anticipate more unpredictability over the coming months, as the Fed’s December meeting approaches. Odds that the Fed will hike interest rates at that meeting are currently over 80% (up from 30% last month), but are likely to remain volatile.

Here are a few data points to watch if you want to know what to expect.

Inflation

Inflation is the most important data point the Fed considers when setting interest rates. Inflation has been running persistently below the Fed’s 2% target for years, but the Fed has hiked rates four times since late 2015 anyway.

[text_ad]

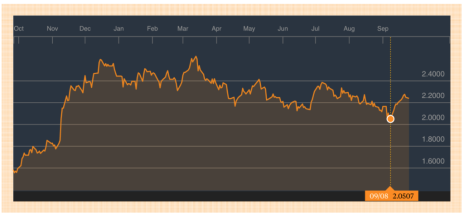

Inflation got close to the Fed’s 2% target at the start of the year, hitting 1.9% in January, but then slowed down. Lower inflation readings over the next eight months contributed to a steady slide in interest rates. In the second week of September, the yield on the 10-year treasury hit 2.052%, its lowest level since the U.S. presidential election (see chart).

However, inflation started to perk up in August, and was expected to accelerate in September (data has yet to be released) due to rising oil prices. Hurricane Harvey forced many Gulf Coast refineries to close, taking about a quarter of U.S. refinery capacity offline and sending oil prices above $50 per barrel for the first time since May.

If inflation falls short of expectations, even with the effect of the hurricanes, interest rates may head south once more.

Employment

After keeping inflation in check, the Fed’s most important job is maximizing employment (these two goals are often referred to as the Fed’s “dual mandate.”) With the unemployment rate down to 4.2% in September—the lowest in more than a decade—the Fed has nearly reached its goal.

Fed Balance Sheet Run-Off

The Fed will start shrinking its balance sheet later this month. The Fed currently holds $4.5 trillion in fixed income securities, purchased during and after the recession to create liquidity and further depress interest rates. When securities mature, the central bank reinvests the proceeds.

Starting this month, the Fed will allow $10 billion in maturing securities to “run off” the balance sheet instead. The monthly run-off will be gradually increased each quarter until it reaches $50 billion per month next year, gradually shrinking the Fed’s fixed income holdings and putting gentle upward pressure on interest rates.

The “Third Mandate”

Some Federal Reserve watchers think the Fed has a “third mandate” that will push them to hike rates again in December, despite low inflation and moderate economic growth. Interest rates directly affect financial market behavior, and the Fed may want to raise rates again to curb speculation caused by easy money policies. While not technically part of the Fed’s mandate, the data backs up the Fed’s (hypothetical) concerns. The Goldman Sachs U.S. Financial Conditions Index measures how tight or loose financial conditions are—is it hard and expensive or easy and cheap to obtain money?

And despite the Fed’s last four rate hikes, the index is now at its lowest level since 2014, indicating that financial conditions remain very loose. That could be part of the reason the Fed seems so intent on raising rates, despite little evidence that the economy is overheating.

Other Factors Determining Interest Rates

Lastly, numerous other factors can push interest rates and rate hike expectations around day-to-day. Last month, North Korean missile tests contributed to rates’ decline by increasing demand for treasuries. Stock markets sold off briefly after North Korea fired missiles over Japan and tested a hydrogen bomb in early September, triggering a scramble for safe assets. Increased demand for U.S. treasuries contributed to a decline in their yields.

Another contributor to rates’ slide last month was the resignation of Fed Chair Stanley Fischer on September 6 (though he’ll remain on the board until mid-October). Fischer is a defender of traditional economic models that suggest inflation accelerates as the unemployment rate drops. With him out, the Fed may lean more dovish.

Two weeks ago, the White House pre-announced a tax cut plan that could substantially increase the U.S. deficit and the supply of treasuries. That would create downward pressure on yields, although the market’s reaction so far suggests that the plan has a slim chance of becoming law.

*This post was excerpted from the September 27 issue of Cabot Dividend Investor. To subscribe, click here.

[author_ad]